Category: Uncategorized

Love, Loss, and Wishes for My 43rd Birthday

It wasn’t easy. It was probably one of the most difficult things I’ve ever endured, and I’ve been through a lot of deep lows in my life. To watch a planned future dissipate slowly in front of me then disappear in a few strokes is painful and heartbreaking. I didn’t know when or how I was going to share the news with everyone, but writing has been a lifesaver for me in my darkest times, so I open my heart to you in this moment. This year I turn 43. It’s a time to celebrate life, even if there has been profound loss this year.

He is a wonderful man with a good heart. He’s done little things for me, big things for me, and all things in between. I’ve tried to do the same for him. But I’ve not been able to do one thing for him that would give him joy at the core of his being. I cannot give him a child.

For months, every day, many times a day, we had sex – for intimacy but also for a goal, to have a child. Doctors said I was fine, a healthy body, and good amh level (measure of ovarian reserve, in other words I was still fertile according to all the tests). By early 2014, we had to do more to find out why I wasn’t conceiving. When we looked inside we found a unicornuate uterus – a uterus with a single fallopian tube, and my one tube was “underdeveloped”. In vitro fertilization was the only way now. If you’ve ever been through IVF or know someone who has, it’s grueling. Drugs are pumped into your body like a firehose dousing a three alarm fire. I gained a ton of weight over the course of time that I went through the cycles. Hormone shots into my tummy and my butt were scary. Once I hit a bad area in my butt, leaving my right leg stiff and throbbing like Sammy Sosa whacked it with a wooden baseball bat. I was literally limping and wincing in pain with every step. I hit so many bad spots in my tummy that I started to collect a large cluster of bruises on my belly. It looked like a rotten piece of meat infested with mold and mildew. Clinic visits were weekly to monitor the body and the expanding ovaries filled with potential eggs to be retrieved. It was amazing to watch the growth inside my ovaries as the dozen or so eggs on each side would swell up like water balloons floating in translucent black and white satchel.

When it came time to retrieve, I experienced a pain that literally left me debilitated. Because my uterus was tilted, the doctor had to pierce it with the catheter to reach my right ovary. In an ideal case, the retrieved eggs are fertilized immediately, and the successful embryos are transferred fresh within days of the retrieval. Because my uterus was punctured, it would need time to heal. Every cycle would have to be a frozen transfer, with the embryos cryogenically frozen until my uterus was ready. The pain of a punctured uterus was excruciating. It hurt so much to just sit up. I literally had to crawl on all fours just to get to the bathroom to pee. I would then crawl back to the bed, resting for a minute on the floor before I could psyche myself up to raise my arms on the bedside and push myself up on it. I then used my shoulders to lift my upper body up onto the mattress, then roll my torso and use my legs to push myself back into bed. This lasted for days.

Fall 2014

Clinic: Negative. You can stop the shots. You’ll get a period in about two weeks. Doctor says you can try again after your next period starts.

Me: Ok, thank you.

I started to cry, a lot. I was a disappointment. Couldn’t fulfill the hopes and dreams for him and his parents. I broke the news to him with huffs and puffs and sniffles and whines.

Me: I’m so sorry. I’ll try again.

There would never be an again like that. The next 3 attempts, I’d never get this close again. One of those cycles the doctor suggested I do an egg retrieval again so as to bank more embryos just in case. So again, same protocol, same pain, same struggle, and same ending – nothing to show for it. No pregnancy. More cycles after that, same result, no pregnancy. By the next summer, I was so tired of being doped up, tired of the side effects of migraines, nausea, and fatigue. And mostly, tired of the bad news.

Summer 2015

His cousin and cousin’s fiancée invited us to a going away party. They were taking off for jobs in Japan. It was a festive Saturday as the multitude of cousins, uncles, aunties, and friends gathered to say their farewells. Only 24 hours prior to this celebration, I was given the news of my 4th failed attempt at pregnancy. Cancelled cycle due to thin lining. The cycle before cancelled due to high estrogen level. The air of failure was still fresh on my breath when the door opened and we yelled the standard, “Surprise!”.

Them: Thank you for being here to celebrate our departure, but the surprise is on you! We’re actually staying. And the reason is because we are pregnant!

A roar of laughter and cheers rang out among the crowd. I was sitting across the room from him. I could see his face clearly. We had not been able to conceive after 2 years of trying, and here, in this moment, his cousins who weren’t even trying were already months along. He didn’t smile, his eyes were deep in thought, I don’t even think he noticed that my eyes were fixed on him. At the food line, my mother-in-law questioned me, surely in reference to the news of the day and the repurposing of this party – a baby shower.

Her: Thao, so what is going on with you and the medical stuff?

Me: I’m sorry, it didn’t work again. I just found out yesterday.

The look of disappointment on her face cut through my chest. I found myself consoling her, rubbing her shoulders, telling her it’ll be okay, that we’ll try again. Now that I look back, I ask myself, who was there to console me? Few knew what we were going through, so I solely relied on him and his parents. My sister cried for me, but I told her that everything would be ok. My parents got the update from my sister, but they know me well enough that they waited for me to reach out to them. As for my partner in this journey, he’s a good man, but emotional outpouring is not his forte. He holds emotions tightly, and he’s an optimist. My deep disappointment of failure was experienced by him as just another step towards the bigger vision he had, which was seeing himself as a father – just like his father, and his cousins, and his friends. And this made my failure to deliver (figuratively and literally) even more stressful. I had big expectations to fulfill, and I hate disappointing the people I love.

Almost everyone’s expectations of a new couple is for them to bring life into the world and create the harmonious imagery of family. Everywhere I went, the routine script played out like a reality tv rerun. “Sooo, when are you going to have a baby?” “Sooo, when is it your turn?” “No pressure, just enjoy each other and it will happen.” I fucking hated these questions and statements. I replied with courtesy, but my inner voice was screaming, “If we were pregnant don’t you think we would share the news? Please stop asking the most socially scripted questions ever!!!” It was almost as scripted as “Hi, how are you doing?” I’m freaking tired of being asked these questions and given these statements every time I go to a family gathering. The one that irritated me the most was, “God will give you what you need when the time is right.” God and Saints play an integral role in my in-law extended Filipino Catholic family. An auntie gifted me with a white scarf that was blessed in the Philippines at a parade of one their saints. It had magic fertility powers so all I needed to do was wear it around my belly like an undergarment. Was this bellywear more powerful than the fertility Saint statue my husband purchased, set on his night stand, and held at night before he went to bed?

The powers of God, Saints, blessed undergarments, and prayers never produced the result my husband and in-laws so badly wanted to see. The compounded swell of emotions at this farewell turned baby shower tore me up inside. I was a sad sack of heartbroken emotions. I was tired. I didn’t want to try anymore. I gave up.

This was the beginning of our end. Within months of this episode, another tornado ripped through our life, but that is another story in and of itself. I promise to expand at another time.

Summer had come, and my annual pilgrimage to my familial roots was in full swing. Being in Texas is like a home that once was, and even though it is home no more, family, friends, and formerly forged memories run abundant in the state where everything is bigger. In the collection of Texas memories, I hold deeply the adventures of being a temporary mother figure to my niece and nephews. Witnessing and experiencing the joys and the hardships of parenting gave me rich perspective on motherhood. I pulled night duties of feedings and diaper changes every 2-3 hours. I cradled and rocked and sang the children to sleep. I went days without a shower. I ate bits and pieces of meals in between duties. I played and fed and bathed and disciplined and loved and loathed the time with these little ones. I felt immense relief when I returned home to California and soaked in the relaxation of work and play and deep, long sleep as a childless woman.

As I reflect on the culmination of everything I just shared with you, I realize that I never thought about being a mom when I was growing up. I know a lot of women who said they so much wanted to be a mom. Me, meh, not a thing on my radar. But what was on my radar was a constant pinging of social expectation. The social expectation was cued by the external forces of a standard timeline and sociocultural recipe that we should follow if we are to achieve happiness. Let me be clear, no doubt, family brings happiness. But in my quest to fulfill this happiness by bringing a child into the world, I woke up to the reality that this happiness is not of my own. It is for others. And that is no way to live. But in the course of the journey, I adapted it as if it were my own because the expectations and social norms are immensely powerful. I told my husband when we met that I could go either way. I wasn’t dead set on having children, but if I did, I would be a damn good mom. He said he wanted children very much. So we agreed, we would have children. We never imagined it would be this difficult. I can’t say that it was difficult for him, perhaps emotionally it was difficult to see your wife going through the turmoil, but to experience the ups, downs, and all arounds of physical and emotional tolls of not delivering the goods was a ride I took alone. The one question we did not ask because we did not anticipate the difficulty of conceiving was, “If we can’t have children, what will we do?”

Him: Why are you giving up? Why are you quitting?

Me: I don’t want to do this anymore. I realize after this whole ordeal and after taking care of my sisters’ babies that I don’t even know if I want to be a mom anymore. I don’t know if motherhood is right for me.

And as the discussions between us escalated, I stood more firm in my place that motherhood wasn’t desirable for me. It was desirable to fulfill his happiness, which is what I’ve always wanted to do. But the truth of my reflection in the mirror is that I don’t feel that being childless should define me. Motherhood doesn’t define me. And this is where we could not compromise. Fatherhood would define him. It is deep in his DNA and identity of how he sees himself.

I went back and forth on the situation. Happiness for me? Or happiness for him? If I make him happy, then that will make me happy. But being a mom is no dip in the pool. It’s a swim across the Pacific to Asia feeling like there’s no life vest at times. How do I know this? I listen deeply. I observe intensely. I hear the stories with heart and ears wide open of mothers all around me. And I experienced just a snippet of childcare in the extended periods of time that I cared for my niece and nephews. There is good, there is bad, and there is ugly. If you are a mom and disagree with me, that’s okay. There are plenty of moms who would disagree with you. Had it been easy for me to get pregnant, I would not be telling you this story today. But it’s been a struggle, and usually I’m not one to quit. I always go after something relentlessly if I really want it. I guess I just don’t want to be a mom that badly.

I wanted my marriage to work badly, though. Divorce is another experience that makes me feel like a failure. The day he was ready to sign a lease and move out of the house, all my strength and fortitude to stand my ground as a woman who didn’t want to bear children were whittled to a tiny grain of sand.

Me: Please don’t do this. I’m sorry. I’m sorry for everything. I’m sorry for the disappointment I’ve put you through. I’ll try again. I’ll call the doctor right away and try again.

And I did. I got the insurance paperwork done. I got the payment ready. I got the prescription ready.

And when my period started, I felt my whole body tense up. My heart started to race while a heaviness expanded in my chest. I was paralyzed and couldn’t do it. Couldn’t take the meds. It made my mind crazy mad to anticipate doing it over again. But more so, a panic state of crippled angst about being a mom. It’s probably the closest thing I’ve ever experienced to a panic attack.

Him: I knew it. I knew you weren’t going to do it. You’re stringing us along. We’re just kicking the can down the road. It’s okay. You have to be true to yourself. And I have to be true to myself. We need to go in the direction of our happiness, and at this point in our lives, our directions and visions of the future are no longer the same.

He was right. He verbalized the words that ran in my head for so long but never had the courage to say. I was chicken shit and even fooled myself into thinking I’d want to experience IVF again just so I could keep my marriage intact.

As I came around and saw the truths before me, he began to wonder if it was the right decision. He suggested we take some trips to rekindle the flame. Perhaps being childless might not be so bad. We went back to San Francisco at the site where he proposed to me. But by then, it was just another place, the emotions were gone, at least for me anyway. I didn’t feel the same. I’d seen the light, and it highlighted the divergent paths we were to set upon. He needed to fulfill his dreams, and I needed to fulfill mine.

Why not adopt, you ask? It’s not only about conceiving a child. It’s about having a child. It’s about motherhood, parenthood, and the life that I’d grown into over the last few years. My mother is a wise person who I admire greatly as a woman and a mother. She said to me, “Perhaps your body did not allow it to happen because your mind and your soul never really wanted it.” I’d never thought about the connection between spirit, mind, and body, and with my mother’s words, the picture became clear. As I envisioned life as a working mom, I felt stressed and afraid that I would be unhappy.

Science makes the clear picture even sharper. As a sociologist, I keep myself abreast of what science reveals about the human condition. Scientific research shows that children make people unhappy. One report of a recent study states, “It’s an almost immutable fact: Regardless of what country you live in, and what stage of life you might be at, having kids makes you significantly less happy compared to people who don’t have kids. It’s called the parenting happiness gap” (Anderson and Pyne 2016). Also note that the study highlighted that American parents are especially miserable, posting the largest gap (13%) in a group of 22 developed countries. The research was conducted by Glass and colleagues (2016) at the University of Texas at Austin and published in the American Journal of Sociology. They point out that this gap is due to the poor family-work policies that exist in the United States. Another study by Margolis and Myrskyla (2015) confirmed the same outcome. A report on that study notes, “that unhappiness stemmed from three main causes: health issues before and after birth, complications during the birth, and the generally exhausting and physically taxing task of raising a child.” Research confirms for me that my idea of happiness is the current state of my life (childless), and the anticipated reality of what I envision as a life with children isn’t something I want (unhappiness).

As I reflect more on this matter, I realize that while I’m not a mother, I’ve become a mother figure to many. My cousin’s daughter calls me her “spiritual mom” and once wrote a report about the person she admired the most – she chose me. Many of my students tell me I’ve given them the hope and belief in them that their parents never gave, one of those students calls me her angel. I have a lot of love to give. I care, and cherish, and nourish those around me who are in need. I believe this motherly/nurturing thing I’ve got is part of my spirit. Whatever reasons that God, Allah, Buddha, the Cosmos, etc has for me for not being a mother, I’m okay with that. I’ve made peace with that. And the reasons for why my spouse and I divorcing, I’m okay with that, too. It wasn’t easy. It’s taken me months to even want to share it openly like this. But people want to know. What happened? You two seemed so happy? And we were. And we are, at least I am. I believe he is, too. I sincerely hope that he is. Enough time has passed for me to heal enough to where I can talk about it as beautiful period in my life and also a lesson to be learned. I’m no longer stuck in my worries and fears about the future. I am living in the future now. I’m making my way forward and living everyday in the way that fulfills me. I don’t know what else the future will hold, but I know that even though I’m not a Mother, I have Motherly Love that I can share and want to share. Motherhood is not about having a child, it’s about the love, care, support, and guidance that we can give to someone who needs and/or wants it. I’m always ready to give, and while I didn’t embrace being a mom, I embrace Motherhood with all its wonder and fulfillment.

I want to see him be a father someday. Last June, Father’s Day presented itself with pictures on social media of male friends and family members with their children. Their spouses wished them a Happy Father’s Day and thanked them for being wonderful. I understand why he sees himself in that kind of imagery. I see him in it, too. And that’s why I believe it will happen for him. I will celebrate that moment for him with the deepest joy… even though that moment will not be with me. I was once his happiness, but life paths change, and his next happiness will be with someone else. The someone who can fulfill his life dreams will be the right one. I was the right one at one point in time. And while it hurt deeply for a moment that I wasn’t the right one anymore, I’ve made peace with the vision of him in his place in this world as he sees it – as a father.

As for me, what do I see for myself? I haven’t really figured that out. Today, at 43, these are the things I wish for… I wish for him to have his dreams fulfilled. I wish that I can continue in my career and grow as a professional. I wish that I will see my niece and nephews grow into their fullest potential. I wish to be bonded with family and friends everywhere. As for a partner, I don’t know. For the last couple of months, I tried to imagine being a single career woman who would do lots of philanthropy, play lots of volleyball, and have lots of lovers and dalliances at my leisure. But that last thought has faded away like the end of a song. I’ve always been a long term thinker, and I can’t see myself doing the leisurely lover thing in the long term. How long can fleeting moments of romance really last? They don’t. I like things that last. Like family, friends, career, philanthropy, and volleyball. So I wish for a strong companionship with someone. I wish to have a best friend be my lover, too. I wish to see an end game where I have that someone by my side with my family and friends as I take my last breath here on Earth. But I don’t know if that will happen. Nothing is for sure. The only thing I can see for myself in that regard is that I will always want to give love, and wishfully, love will be returned to me.

What Stirs My Soul

Today is his birthday. He would have been 43.

We met at age 19 in college. He had a warm and friendly aura. He was one of the most generous persons I’d known, and even to today, I have yet to meet many who match his level of giving. He confessed his amour at age 25, even though our friends knew it had probably been there since day 1. He was mature and committed. I was neither. I entertained the idea, even followed through with “taking a chance”. But in the course of only two months, I was already eyeing my options and living out my “play the field” mantra. He was forgiving, persistent, and patient. I foolishly believed if I kept him within distance, that one day I could fall for him. This is the kind of advice from friends that was a constant in those days…

Me: “I see him like a friend. I don’t want to ruin what we have. What if it gets ugly, like most relationships do when they go sour?!”

Them: “He’s the kind of guy you marry. He’s not exciting, but he’ll be really good to you. He’s always good to everyone. Imagine what he’d do for the One he’s in love with!”

Me: “Maybe someday. Right now, I’m not even thinking about getting married. I just wanna have fun!”

Years would pass. He was there for me. I was there for him. One year, he was short on money for tuition. I didn’t even have to think twice about it. I paid it with my summer work money. He’d changed his major from engineering to nursing. He eventually became an emergency room nurse.

After his first month at work, he paid a visit. I wasn’t home, but my mother was. When I came home that evening, my mother gave me a talking to.

Her: “You know I taught you that you can’t take gifts from any guys. They will expect things. You have to make your own money so you don’t rely on anyone for anything. Your friend came by today and left you this.”

Me: “I thought you said I couldn’t accept any gifts from a guy?”

Her: “He told me you helped him pay for school. He’s got a job now. I’m proud of you for helping him. When someone gives you a gift to say thank you for doing something for them, you must accept it graciously.”

I untied the silky red bow wrapped around a cream colored box lined in bright red velvet. The word Omega was etched on the box. A bright and shiny timepiece with sparkling diamonds in the bezel was snuggled around a small pillow in the same bright red velvet color. A note fell from the lid.

“Dear Little One, thank you for being there for me in every way. You’re the best kind of friend anyone could ask for. Please take this gift as a token of my appreciation. Consider it a repayment of my school loan from you, with a little interest. Love You Always, XXX”

He grinned widely when he saw it on my wrist at dinner. We had a long conversation about the meaning of life and what the future held for each of us. We’d be best friends, always. We jokingly made a pact – that if neither of us had anyone by the time we were 30, we’d marry each other. At the age of 25, 30 years old seemed really old to me and a good age to be married to your best friend.

He got his new apartment near his work. I borrowed my dad’s van and chauffeured him to Ikea. He bought a ton of stuff – living room, dining room, bedroom, entertainment center, and even decorative items. We hauled it all in the van and spent an entire weekend assembling every single item. When we were done, we kicked back on his couch and admired his fully furnished crib.

He leaned over to kiss me, and I let him, for a second, maybe two. But I couldn’t continue. I had a boyfriend at the time, one that I was about to dump anyway. He had a bad temper and was extremely jealous and controlling. I kept thinking he would beat up my best friend if he found out we kissed, even if for a second or two. I jumped off the couch and said, “Please don’t mess up our friendship. I won’t tell XXX about this. Enjoy your new place.”

Out of fear, out of confusion, out of awkwardness…out of whatever it was, we didn’t talk for months after. Then suddenly, these conversations started swirling among our mutual friends…

Them: “Did you hear? He has a girlfriend. Some girl with 2 kids! XXXXX already met her. He can’t stand her. She’s so not right for him. You’re his best friend. You need to talk some sense into him!”

None of our friends knew about our awkward moment on his couch and that we hadn’t been in touch for months.

Me: “Don’t judge her yet. We don’t know her. I trust him. I’m sure he wouldn’t be with someone terrible.”

I wasn’t jealous. But I was certainly curious.

Me: “So who’s the lucky girl?”

Him: “She’s been dealt a really bad hand. She’s great and she’s totally into me. She comes over a lot, cooks for me, and we have a great time together.”

Me: “Is she hot?”

Him: “Definitely.”

Me: “Our friends who’ve met her aren’t thrilled that she’s got two kids. Are you ready for that?”

Him: “Definitely.”

I should have known it would get serious quickly. He’s not the type of guy to fool around. I called him one early Saturday morning and invited him to lunch to investigate further. His voice was groggy, obviously I’d woken him up.

Me: “Hey, you wanna grab lunch today?”

Him: “Maybe another time. I’m busy today.”

Me: “Oh ok. What are you up to?”

Him: “XXXXX is with me.”

Me: “Like right now? As in next to you as we speak?”

Him: “Yeah.”

Me: “Ok. Well enjoy the rest of your day!”

She was sleeping over. It had gotten way serious. He eventually married her, against all advice and persuasions by many. The wedding was beautiful. We were all there to support him, even if we didn’t feel she was right for him. His parents weren’t all that thrilled, to say the least. His mother spoke with my mom at the reception. “Your daughter is the one that got away. I wish it was her.”

I was hoping to become friends with her, but she kept her distance from me. The looks she’d shoot at me with a side eye were obvious to everyone. My bubbly greetings were always met with a quick glance and an even quicker “hey” under her breath.

Me: “Why doesn’t she like me? Does she have something against me?!”

Him: “Yeah, she’s not comfortable around you. She says I act differently, even speak differently when you’re around. I don’t know. I guess I shouldn’t have told her you were my first love.”

Me: “Ugh, you moron! Why did you tell her that?!”

Him: “Because she asked me why we were so close. Since I love her, I wanted her to know the truth.”

He was so naïve. And I was prideful. More so, I was frustrated with his optimistic, nice-guy attitude that believed she and I could get along if he was truthful to her. It only made things worse.

Me: “Ok. So for the sake of your marriage and your happiness, I think it’s best we not talk anymore. So much for being best friends forever. I guess you have her now. She can be your best friend.”

Him: “She’s my wife. I love her. But I love you, too, but as a friend. I don’t want to not be friends with you, though.”

Me: “Too bad. It has to be this way. Take care of yourself. Bye.”

That was the last time I ever heard his voice again. We were already in our 30s. Our pact deadline had passed, and now our friendship was over.

Through friends, I learned that he had a child with her. He put her through nursing school, bought her a fancy car, a nice home, vacations, the works. One big happy family. I was happy for him. I was forging my own happiness and was relieved that maybe we were wrong about her.

October 2009, he sent me a Facebook friend request. On the day of my birthday, October 19, instead of posting a birthday wish on my timeline, he posted on his own that “things don’t turn out the way you’d imagine.”

I was afraid to initiate contact with him. What if she reads his stuff? What if she sees my “likes” or my comments? I’ll just wait for him to reach out to me. He never did on Facebook. I had to wait another 2 and a half months to hear from him.

December 31, 2009. I’m in Houston for the holidays and ringing in the new year with my siblings and cousins at the house my parents bought for us. They stayed in the house we grew up in, and we got this nice pad to ourselves. In my bedroom, I have a white cardboard box filled with mementos and keepsakes. Many of his cards and notes were in there. My little cousin Vinnie came downstairs around midnight as the ball in NYC dropped. He had a purple envelope in his hands and showed it to me.

“Auntie, what is this?”

I looked at it. It was from him, a birthday card with the same salutation as all the other notes and cards, “Dear Little One”. I got really sad when I read the last line, “We will laugh until we’re old and gray.”

“Vinne, why did you give this to me?”

“I don’t know.”

January 1, 2010.

Them: “He’s dead. I can’t believe it. He’s dead.”

Me: “What?! No, are you sure?!”

After hearing it enough times, it started to sink in. He was gone. He’d taken his own life. And he took a part of me with him. My gut was sucker punched. The blow was the kind of pain that induced vomiting, and I’d never cried with such anguish as I did in the days after. I was full of regret. Regret that I ended our friendship. Regret that I didn’t initiate contact after we made our social media connection. Regret that my pride and frustration got in the way of being mature enough to work through the struggles of seeing a friendship through even if his wife didn’t like you. Regret that I held out during all those years – when I wanted to just say “Hi, how are you doing? – and not in a superficial way, but in a genuine way of really wanting to know. Is your wife being good to you? Are you happy? Are your kids happy and healthy? Do you miss me? Because I sure do miss you. I miss our talks. I miss our walks. I miss the bets we used to make playing pool in the University of Houston game room in between classes. I miss giving you shit for loving me. I hope she’s brought you happiness. I hope she made you feel like you’re the best guy in the whole wide world.

But if so… if you were happy, then why? Why did you let her treat you that way? Why did she abandon you when you had done nothing but given her a better life than she could have ever imagined? Why did you leave us? Why did you not reach out to me? Why, damn it?!

Because I was firm, our friendship was over. This was all my fault!

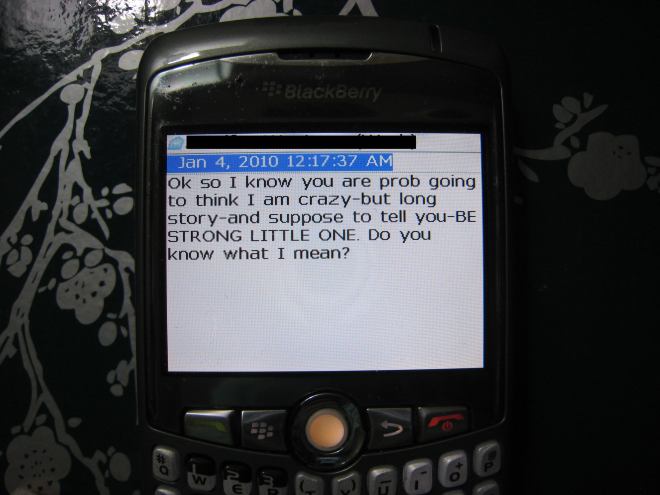

Hunger and slumber eluded me for 2 days until my body shut down. I eventually crashed into a deep sleep, only to be awakened shortly after by a text message on my Blackberry.

This message came from a student in my class when I taught in 2006 at Pikes Peak Community College in Colorado Springs. Initially, I was dazed, confused, and spooked (to say the least). How could this be? She could never have known that he ALWAYS addressed me as “Little One”. I shed tears as I type this now and look at the message that is black and white in front of us. This was his message to me. He did reach out. And he used this young lady who was my former student, who had my number because she spoke to me only 6 months earlier about going to graduate school, as his messenger. What a paradigm shift for me in the way I understand life, death, and the meaning of the soul. And in the moments after my thoughts settled and I had a long conversation with the messenger, I was at peace. All the pain, the anguish, the sorrow, the regret…they all washed away in an instant. Calm, love, peace, resolution – these feelings were running through my veins and spiritually cleansed me of any regrets and misgivings.

I wanted to tell his parents, but I had not spoken to them in years. I didn’t know how to reach them. The next night, I had a dream of an old cordless phone with the digital display. 281-XXX-XXXX. It was clear and obvious. Their home phone number had been delivered to me in my dreams. I shit you not.

My visit to his parents was not sad. They listened with compassion and appreciation. “We know he always loved you. We’re not surprised he reached out to you. Thank you for being his messenger.”

Their Buddhist beliefs and their Vietnamese cultural knowledge affirmed the understanding of an afterlife, where our loved ones communicate with those they love and cherish.

Needless to say, this changed my world view. I believe that there is indeed another plane of our existence. I believe myself to be rational thinker, a lover of science, and a champion of the scientific method. But this experience has shaken me and shifted my world view regarding the afterlife. My soul is connected to his. Over the years, I’ve received signs from him, but only on my birthday. My bedside light flickers. My television turns on. One area in my room gets very cold. These moments are treasured. And in moments like tonight, when I’m reminded that it’s his birthday, I write this to send my energies to him, and to share with you something in my life that truly stirs my soul.

Guns, Roses, and Wars

Most of us know it as the Vietnam War. On the other side of motherland, it’s known as the American War. Two sides of the same coin can whisper millions of harrowing tales. Some are told as immigrant stories, while others are told as war stories. This is a tale I would have stored in my memory as just another story among those millions. Mine is not unique, I believe. Mine is not more important, nor more compelling. We all suffered trauma in one form or another. And we are here now, doing our best, as we all do, to toil the daily grind of life in America. But had it not been for the encouragement of those who simply stated, “Thao, you need to write”, this tale might have never been told. Thank you to those encouraging friends. I tell this for the woman and the man in this story who will never understand the depth of their sacrifices. I don’t think they’d understand because for them, it was not a choice. It was thrust upon them by the motivations of political power structures that they, nor we, may never truly understand. It’s not because we don’t have the capacity to do so, but rather, it’s because we are in the dark. Governments and their puppets work undercover as secrets of war and plundering are best kept in the clandestine shadows, hidden from public knowledge. In the lines of Guns ‘n Roses, war “feeds the rich while it buries the poor. Your power hungry selling soldiers in a human grocery store.” The war machine affects us all. This is the story of one family, among millions, whose lives were catapulted out of their homeland by the power machine of war.

In the darkness of April 30, 1975, a South Vietnamese air force pilot was in a frantic search for his wife and child. He completed his last mission, a supply drop from his C-130 Hercules, and he had to find them because he knew the end was near. Mother and daughter were hiding in a hangar at the Tan Son Nhat airport. What or who they were waiting for, they did not know for sure. Where they would run to next, they did not know at all. They’d already run from Can Giuoc, the mother’s countryside hamlet battered by Operation Concordia, and they’d already run from Saigon, a cityscape in ruins from gunfire and bomb blitzes of the Tet Offensive. It was the two of them, baby girl in her Mama’s arms, waiting with a crowd of other women and children. Although it was near midnight, baby girl’s Mama could not sleep. She had not slept the night before. No one sleeps when running from death. She squinted her eyes toward the opening of the hangar, and she could see the flashlights flickering. She heard the recognizable voice calling to her in desperation. He’d found them, but there was no time for explanation. He grabbed their one small suitcase of belongings, and she wrapped baby girl tight in her arms as they sprinted out of the hangar and onto a jeep. Baby girl was tired and sleepy. She was recovering from an infection and had no strength to even muster a cry.

The jeep had several other passengers, and as it sped towards a haphazard row of C-130 planes on the runway, a thunderous flash of fire burst in front of it. The passengers jumped from the jeep to escape the blaze. Mama leapt with baby girl in her arms. The jolt of a hard landing on her knees stung in the moment. As she rolled to her feet, she felt the hard blow of her husband throwing his body on top of her and baby girl, taking the shrapnel into his back and arms. There was no time to feel the physical pain nor to assess the wounds. They got up and just kept running. By now, the columns of fire blazing around them lit up the runway. All the planes were fueled, and it seemed they had a choice of which one to board. But in an instant, a hail of fire rained on one of the planes, combusting its nose. In what seemed to be a counterintuitive move, Baby girl’s Father led them toward the burning plane. Those who ran in the opposite direction were soon enflamed by a direct hit. There was no time to feel the emotional pain nor to assess the dead. Had baby girl’s Father not made that split second decision, this story would not be told today. He figured the area of the burning plane, once hit, would be less likely to be hit again.

They made it on to an in-tact plane along with roughly 300 passengers. The air inside the cargo plane was dense, filled with the reek of blood, sweat, and tears. Baby girl was hungry and thirsty, but she was too tired to cry. Her eerie silence and pale skin worried her Mama. Her Father’s pilot buddy noticed her sickly face, too. He pulled a grapefruit from his bag, peeled it quickly, and squeezed the juice of life into her mouth. She began to move once again, and her Mama cried in relief that her baby girl was still alive.

Con Son Island is infamously known for its “Tiger Cages” published in Life magazine in 1970. The abused and tortured prisoners who were shackled in literal tiger cages were nowhere in sight when the 300 passengers stepped foot on the island. It was nearly 3:00 a.m. The women and children were told to stay while baby girl’s Father and the other men planned to return to Saigon for the next battle move. Before they completed their plans for a return point of landing, they were radioed by their commanders to remain on Con Son. Within hours, dawn had set upon them, and they received orders not to return. And just like that, it was over. It was the end. They lost the war. They lost their country. The sinking feeling in their stomachs was born from swallowing the bitter pills of anger, grief, and disbelief that only refugees fleeing destruction in their homeland can understand. Throughout human history, there are too many who understand. And like those many, all they had left was their will to live. They disrobed from their pilot gear, changed into the civilian attire stuffed in their bags, and left their guns and other weapons behind. The women, like baby girl’s Mama, were relieved they would not be separated from their men. But their relief was swirled among fear, confusion, and worst case scenarios in their hearts and minds. Baby girl’s Mama thought of her own parents and seven siblings as her eyes fixated on the streams of crimson on her pants that flowed from the bloody gapes of her kneecaps.

They made contact with a flight landing operator in Thailand courtesy of the country’s “gentleman’s agreement” with the U.S. government. Under the deal that began in 1961, over 80% of U.S. airstrikes on North Vietnam were conducted from these bases named Royal Thai Air Force bases. By 1975, the operations on these bases were receiving planes that carried refugees like baby girl and her parents. They were processed there and shuffled on to a refugee camp in Guam through Operation New Life, a program sanctioned by and financed through the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975. They were fed and housed in a tent among thousands of other tents which came to be known as tent cities. After processing for resettlement, baby girl and her parents were told they would be going to America via Eglin Air Force base in Florida. It was there that baby girl’s Father made contact with a sponsor, a widow from Randolph Air Force Base in Texas who befriended him and his Vietnamese unit buddies when they trained there in 1968. She took in the family of three along with all the young men in the unit.

It was an attic, but at least it was shelter. It was stable, and it was home. Baby girl stood at the window staring outside at the neighborhood sisters Verle Anne and Verle Lynne. A truck pulled into the driveway, and baby girl’s Father hopped out of the bed. He said good-bye to other men whose faces, like his, were weathered from the hard pressed Texas sun. His 12 hour days on a watermelon farm were enough to live on for now. His pilot logs were rubbish in the burnt garbage of war’s aftermath. Without the logs, he had no proof of flight hours, and therefore, no documentation that he could fly a plane. His airline pilot job would never transpire. Instead, watermelon farmer, construction laborer, machine operator, and finally machinist would line his resume. Baby girl’s Mama spent her days caring for her and cooking meals for the Vietnamese refugee men who had no wife, mother, sisters, or female presence in their new lives. She also took on a part time job cleaning homes in the neighborhood. She walked everywhere – to the homes she cleaned, to the grocery store, to the dollar store, etc. with baby girl in tow. Baby girl walked with small but hurried steps to keep up with her Mama. Mama, even today, tears up at the memory of baby girl’s blistered and bleeding feet. Baby girl never cried nor complained when the metal buckles of the donated shoes that were two sizes too small dug into her tiny but swollen feet. When Mama saw the wounds, she lifted her child and carried her, pushing past her fatigue to make their destination. As the days went on, it was harder and harder to hold baby girl. Mama’s pregnant belly was getting too big. She thought she was further along than she really was because she didn’t know there were twin girls swirling in her womb. Baby girl eventually would have to keep walking on her own. She was tough enough to make the walks with Mama, but the occasional sounds of sirens in the streets sent her dashing under the bed. Her Mama knew the sounds of war scared baby girl, and she worried she would always be a frightened little girl.

At the end of 1976 they moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where baby girl’s Father found a new job through one of his pilot buddies who was taken by a sponsor family there. The identical embryos were now babies, and they were taking up Mama’s time. Left to her own devices, baby girl learned some of the hard knocks of life in the projects of Knoxville. It was here that she learned the sting and aches of kneecap wounds, like her Mama before her. A black girl in the project apartments was baby girl’s first friend. She owned an original Big Wheel, and she was nice enough to let baby girl ride it. She even pushed her along because her legs couldn’t extend far enough without her butt scooching up into the front of the seat into the front bar, which made for an uncomfortable first-time Big Wheel ride. The movement of a bike was something baby girl enjoyed. She relished the speed and the air whipping in her face. She relished it a bit too much and didn’t slow down when she approached the concrete slope heading downhill. She thought it might be fun to go downhill. The concrete did not forgive the skin on her knees as she tumbled out of the Big Wheel and into the pavement of the apartment parking lot. The crumbles of the concrete pebbles dented into her palms. She brushed off the debris and ran home, leaving the black girl and her Big Wheel at the bottom of the hill. Mama was not mad at her, but it must have triggered the memory of her jump from the jeep because Mama held her very tight and cried.

The following year they moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Baby girl’s brother was born there, and Father David baptized him and gave him a Western name. He would be the only sibling among the four of them with an “American” name. They lived in a one-bedroom place on the second floor of a wooden exterior duplex. Baby girl would skip along down the wooden stairs to play with her friends. On an icy afternoon, she saw her friend slip on one of the steps and tumble down with a soda bottle in her hand. The bottle cracked, and a shard of glass lodged itself in the girl’s eye. The blood was thick and dark. Baby girl ran upstairs screaming to her parents. Her friend would lose her eye. The American doctors were nice enough to give her a glass eye for free since her refugee parents had no money and no medical insurance to pay. Baby girl’s Mama made her promise that she would go down the stairs slowly and never carry a glass bottle. Baby girl really liked going to pre-school in Cedar Rapids, but she remembered Mama’s words and her friend’s bloody eye so she never rushed down the stairs to catch the school bus. She liked riding the bus, even if it was in the cold. She liked learning, even if she had to learn while wearing the same outfit twice a week. She liked school so much that when Mama kept her home because she was sick, she would cry. There was only one time she didn’t cry because she had to stay home from school. The night before, she did not sleep well because an intruder broke into the bedroom where Mama was sleeping with all four babies. He pried the window open, but it was a hot summer night, and the large, square, metal fan Mama placed in front of them was also in front of the window. He knocked over the fan, alarming Mama who then screamed when she saw a pair of large and strange eyes staring at her. Baby girl’s Father was sleeping in the living room and ran in to the bedroom, ready to confront the intruder. The lucky stars were out that night, and the intruder jumped out the window, down the ladder, and ran off into the darkness. The police came that night. Baby girl understood some English by then. She remembered the policeman told her Father to put glass bottles by the windows so that if a intruders were to try again, they would knock the bottles over. It was a makeshift poor people’s version of an alarm system. But the glass bottles reminded baby girl of the bloody eye. She was afraid to sleep in the room, but she was even more afraid of an intruder. She would have to sleep in the room anyway because it was the only one they had, but she stayed far away from the glass bottles that acted as alarm system.

By the time they moved to Houston, Texas, in 1978, they still couldn’t afford a real alarm system. But they didn’t think they’d need one. Baby girl’s Father landed a good job as a machinist at Lynes, Inc. Baby girl’s Mama got a job sewing newborn tees for a contractor to the city’s hospitals. Through her meticulous work, an ophthalmologist hired her to manufacture his surgical eye patches designed for cataract surgery patients. It would launch the family into a place where immigrant entrepreneurs might dream of. The house they bought was in a modest working class neighborhood with four bedrooms and two baths. Baby girl got her own room, the twins shared theirs, and baby brother got his. Baby girl no longer rode the bus because she could walk to the nearby elementary school every day. It would seem they were on the path to a life rebuilt for happily ever after. By the standards of the American Dream, they had made it. But the struggles had only just begun. Refugees will always be foreigners who straddle the multi-layered cultural artifacts of two worlds. Baby girl’s life would be filled with strife from the underpinnings of racism, sexism, classism, and all the other ugly -isms that are part of American life. You’d think that making it out of war together would bring a couple closer, but baby girl’s parents were under the duress of life in America. Extended family issues crossed transnational borders and seeped into their daily lives. Often, baby girl’s Father would wage his own battle against the women’s movement tide that was slowly washing away his patriarchal privileges, and his socially learned instinct was to preserve his privilege. Baby girl’s Mama suffered tremendously under the patriarchal extension of her husband’s siblings who later made their way to America. It is why to this day, baby girl is distant from those “family” members. She witnessed the familial tornadoes that wreaked havoc on her parents’ lives and her own upbringing. It was never a quiet household. But in the bustle of homemade culture wars, there was also the hustle of a family trying to make their way in this new land. They worked their asses off. They always paid their taxes. They took in strangers, clothed them, housed them, fed them, and without hesitation, shared whatever they had. They went to church. They tithed. They played volleyball together. They ate dinner as a family almost every night, and they had loud parties filled with dancing and singing almost every weekend. They were social and so beloved by their circles of friends that when their daughters married, the wedding guest lists toppled past 750. Life has been beautiful, but not without its moments of darkness. With the good comes the bad. It is the balance of the yin and the yang. Every rose has its thorns.

Over the course of time, I, baby girl, found my own way to wherever I am now. One of the roads less taken by those around me is the path of work centered around social justice. Looking back on 41 years in America, there are many heroes and heroines among these stories. But among those honored in the stories of 41 years, I’m disappointed in the typical Vietnamese American coverage of it. If it seems to be an act of throwing shade on shared images of the Flag, the candlelight vigils, the grainy photos of the last days, and the other overplayed themes of the war, then those who perceive it as such are limited in their scope of what the mainstream media would like us to put out there. It is disappointing that very few in the Vietnamese American diaspora have mentioned the death of Reverend Daniel Berrigan. He passed away at age 94 on April 30, 2016 – the 41st anniversary of the Fall of Saigon. Reverend Berrigan was known as the radical priest. To me, his work is inspiring, not radical at all. Berrigan was a staunch activist against U.S. involvement in Vietnam. He was imprisoned for burning draft files in a protest against the Vietnam war. He, along with other anti-war protesters, entered a draft board in Catonsville, Maryland, in May, 1968, and removed records of young men about to be sent to Vietnam. They took the files outside and burned them. Reporters were given a prepared statement by the Reverend and his group stating, “We destroy these draft records not only because they exploit our young men but because they represent misplaced power concentrated among the ruling class of America. We confront the Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country’s crimes.” This was a powerful statement then, and it resonates with me now. As a Vietnamese refugee, those words claim my heart for his bravery to call out the injustices of the war. As an American citizen, those words claim my spirit for my own courage to call out the injustices of misplaced power concentrated among America’s power elite. It is with fierce conviction that we must carry on the spirit of Reverend Berrigan. I don’t know if Reverend Berrigan ever listened to the music of Guns ‘n Roses, but if I ever meet him in the afterlife, I hope to share a cup of tea with him while we listen to Guns ‘n Roses “Civil War” together –

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.

Some men you just can’t reach…

So, you get what we had here last week, which is the way he wants it!

Well, he gets it!

N’ I don’t like it any more than you men.” *

Look at your young men fighting

Look at your women crying

Look at your young men dying

The way they’ve always done before

Look at the hate we’re breeding

Look at the fear we’re feeding

Look at the lives we’re leading

The way we’ve always done before

My hands are tied

The billions shift from side to side

And the wars go on with brainwashed pride

For the love of God and our human rights

And all these things are swept aside

By bloody hands time can’t deny

And are washed away by your genocide

And history hides the lies of our civil wars

D’you wear a black armband

When they shot the man

Who said, “Peace could last forever.”

And in my first memories

They shot Kennedy

An’ I went numb when I learned to see

So I never fell for Vietnam

We got the wall of D.C. to remind us all

That you can’t trust freedom

When it’s not in your hands

When everybody’s fightin’

For their promised land

And

I don’t need your civil war

It feeds the rich while it buries the poor

Your power hungry sellin’ soldiers

In a human grocery store

Ain’t that fresh

I don’t need your civil war

Look at the shoes you’re filling

Look at the blood we’re spilling

Look at the world we’re killing

The way we’ve always done before

Look in the doubt we’ve wallowed

Look at the leaders we’ve followed

Look at the lies we’ve swallowed

And I don’t want to hear no more

My hands are tied

For all I’ve seen has changed my mind

But still the wars go on as the years go by

With no love of God or human rights

‘Cause all these dreams are swept aside

By bloody hands of the hypnotized

Who carry the cross of homicide

And history bears the scars of our civil wars

“WE PRACTICE SELECTIVE ANNIHILATION OF MAYORS AND GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS

FOR EXAMPLE TO CREATE A VACUUM

THEN WE FILL THAT VACUUM

AS POPULAR WAR ADVANCES

PEACE IS CLOSER” **

I don’t need your civil war

It feeds the rich while it buries the poor

Your power hungry sellin’ soldiers

In a human grocery store

Ain’t that fresh

And I don’t need your civil war

I don’t need your civil war

I don’t need your civil war

Your power hungry sellin’ soldiers

In a human grocery store

Ain’t that fresh

I don’t need your civil war

I don’t need one more war

I don’t need one more war

Whaz so civil ’bout war anyway?

The Mirror Selfie

Psychologists Jean M. Twenge and W. Keith Campbell concluded in their 2009 book, The Narcissism Epidemic: Living In the Age of Entitlement that, “we are in the midst of a narcissism epidemic.” One of the studies they examined showed that among a group of 37,000 college students, narcissistic personality traits rose just as quickly as obesity from the 1980s to the present. Frightening…we have an entire generation of people who suffer from COW disease… they see themselves as Center Of the World. One of the behaviors associated with Millennials and their COW disease is the selfie, the picture you take of yourself. To add to the effect, we have the mirror selfie. The mirror has been the symbolic tool to measure vanity. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the prettiest of them all? The mirror selfie, hence, is the love child of modern technology and vanity.

I’m classified as Generation X, and I suppose I’m not too far away from Millennials. So why do I find the mirror selfie ridiculously despicable? Shouldn’t I be the bridge that closes the gap between perplexed Baby Boomer and self-obsessed Millennial? Shouldn’t I, at the least, understand the desired effect of the mirror selfie as something that is, at the minimum… a useful tool to share a piece of oneself to a wider audience? Well, I don’t. I find it despicable and annoying. I have a friend on Instagram who constantly posts mirror selfies at the gym. Ok we get it, you’re getting fit. But dayum, every single post has to be the same mirror selfie pose? It gets old as an audience. And it makes me think you are full of yourself. Why are you so freakin full of yourself?

Now that you know how I feel about mirror selfies, allow me to provide a confession. Today I took my first mirror selfie. For reasons undisclosed, I stood in front of the bathroom mirror and took a picture of myself. I even smiled. No pursed-up lips, no side profile turn, no skin exposure (I was wearing work clothes)…quite a plain vanilla mirror selfie. I didn’t post it to any social media site, nor did I use it as a profile picture for any accounts. I sent it to one person, with a note that this would be my only mirror selfie ever. He replied with a compliment, and it felt nice. Hell, let’s be real here, it felt really nice! Imagine the multiplication factor of feeling nice from 100 compliments, or 1,000 compliments, or … you get my point. And now I get it, too. These Millennials are playing out Charles Cooley’s Looking Glass Self Theory of Everyday Life. Cooley explains that “the ‘I’ of common speech has a meaning which includes some sort of reference to other persons is involved in the very fact that the word and the ideas it stands for are phenomena of language and the communicative life. It is doubtful whether it is possible to use language at all without thinking more or less distinctly of some one else, and certainly the things to which we give names and which have a large place in reflective thought are almost always those which are impressed upon us by our contact with other people.” In this theory of identity formation, our identities are not our own. They are a product of contact with others. And in a postmodern society, contact with others is anywhere and everywhere. It is no wonder young people take selfies en masse. They’re soliciting the feedback that we all crave as we search, seek, and shape our identities. So while psychologists explore the sense of entitlement gleaned from examining the selfie obsessed, sociologists need to be assessing the sense of fulfillment that the selfie obsessed experience when they get feedback from others. Because, seriously, who takes a selfie for themselves? What is the point of capturing yourself on camera, just for yourself? We mostly do it for others. I can postulate that the selfie (avec or sans mirror), while leading to narcissistic personality traits, can serve some purpose other than self absorption. And that is the task of the sociologist, to explore the selfie not as an act of self, but an act for others on behalf of the self.